I remember a boy named Tony Yee. His father was estranged, and his mother remarried. Her name was Judy Nathan.

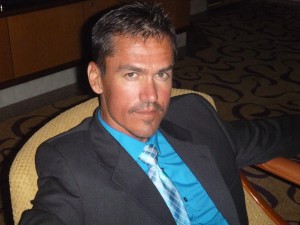

Tony and I first met in the sixth grade. His family moved in next door from California, and he was an only child. Their’s was a small ranch-style home on the corner of First and H Street, in a poor mill town in central Oregon. Tony’s stepfather was an American Indian, and worked at the Warm Springs Indian Reservation some twenty-odd miles north of our town. His mother, Judy, worked as a cashier at a local convenience store.

Our town was barely on the map, the census back then around 1,500 residents, a place where everyone knew your business. Buses ran to and from school, but it wasn’t uncommon to take to foot and walk. The junior high was a stone throw from our neighborhood, the high school a bit further. Oftentimes we stopped by the grocery store before or after school, drinking sodas and playing video games. Astroids was all the rage, and Defender. On the weekends we hunted for soda and beer cans, and exchanged these for nickels. When we weren’t in school we threw rocks along the rivers, and when in a more daring mood we crossed the train trestles that lay several hundred feet above the gorge, listening for the distant horns from encroaching locomotives.

We both came from broken homes, but never spoke of this unseemly bond. We needed escape, and found it in each other, running the streets in innocent games of tag or kick the can, down at the school at the outdoor basketball hoops. Fashion was unheard of, but we tried like hell to be cool. Upon entering high school, we succumbed to peer pressure and smoked weed and drank beer. No one told us that we couldn’t. My grades slipped, and his fared even worse. But what did it matter? The future was a luxury that we couldn’t afford. However, there were times when Tony talked about becoming a garbageman in San Francisco, the city from where he moved. A friend of the family was making fifteen bucks an hour, and after thirty years planned on retiring with a life-long pension and money in the bank. Sadly, Tony’s dreams were better than my own.

My sophomore year was dark with drugs and alcohol. I look back now and hate the kid that I was. He was everything wrong with society, a rebellious loser, having spent a few too many nights in the county jail for offenses that no parents ought to be proud of, and mine weren’t either. Mostly, my parents were indifferent, because dad had problems of his own. No, he wasn’t an alcoholic or abusive. Dad was slowly dying, and toward the latter years it became rather ugly. Pain medication wasn’t helping, and my mother had had enough, was slowly losing her mind. The family was unravelling, and so what did it matter that I turned to alternate means of managing the pain that was my own?

In the summertime we worked for the local farmers, moving irrigation pipes or hoeing mint in the myriad fields. We spent our money on clothes, shoes and drugs. To pay off our debt to society, a judge ordered us to community service, wherein we spent a good portion of the summer washing county cops cars or cleaning the horse stalls down at the fair grounds.

Halfway through our junior year he and his mother moved back to San Francisco. We kept in touch with phone calls and remained rather close. That summer, we convinced our mothers that it would be in our best interests if he moved in with my family to finish out high school. What happened then was inexcusable. Our behavior was not something that I am proud of, and never would I allow my children the mere thoughts of such criminal antics. We took to drinking and driving, stealing cars and money. We fought with whomever wherever, and avoided the law by flight of foot or by car. My grades plummeted, and so did his. My senior year was the glitch in the DVD, a fragmented schism, but I know that it existed. I have the yearbook to prove it, and there I am in the photos. And there’s Tony, and oftentimes we’re standing together.

Judy drove up for graduation, and discovered at the ceremony that her son, Tony, wouldn’t be graduating. He had missed too many classes, and his grades were abysmal. How I managed to squeak by remains a mystery, for I had Fs of my own. Tony went home with his mother, back to San Francisco, and I never heard from him again.

Dad was near death, and I had to get away. From everything. From the town and from my family, from all the influences and the drugs, and start life anew. I took the remedial classes at Oregon Tech, and eventually earned credit hours that could be applied toward graduation. My head cleared, and then my body. How I went from one extreme to another I’ll never know. A guardian angel? Some internal drive that didn’t awaken until I turned 18? Oftentimes I wonder on my younger years had I not met up with Tony. Was he the catalyst for my near destruction? Was I his? Or were we simply bad together?

When I graduated from Southern Oregon I joined the Marine Corps. My head was clear and my heart was strong. The trials of Officer Candidate School were nothing compared to those that I had grown up with. From Quantico, Virginia, they sent me to flight school in Florida – the beginning of a career in aviation. I’ve travelled the world, and I believe that as a United States Marine I’ve done some good. Perhaps enough to balance me out; perhaps enough to make me whole.

Late last year, in 2013, an old high school friend sent an email. “Look up Tony Yee,” he said, and so I fired up Google and went to work. His full name is Anthony David Yee, and I found several articles in different northern California newspapers. From high school, Tony joined the Marine Corps, but from what could be gleaned he ran into trouble and was soon forced out. From there he spent time in and out of prison, until years later he found himself homeless and alone. According to an article, Judy wanted nothing further to do with him. She was living alone. One day she left home for work. Later that night, upon returning, she found her son waiting …

… a man of forty five …

… my best friend growing up.

Several days went by, and Judy failed to show for work. Her coworkers phoned the police, and informed them that Judy was afraid of her son, who had showed up out of the blue days ago seeking shelter. The cops went to her house, where Tony answered the door. Inside, the cops found signs of a struggle. They arrested Tony, and eventually found Judy.

In court, Tony confessed to murdering his mother. At first he attempted to strangle her with a rope. When she successfully fought him off, he grabbed a ball-peen hammer … and went to work. That night, he drove around looking for a place to hide the body. Out of ideas, he returned to his mother’s home and stuffed her body down a neighbor’s septic tank. A judge sentenced him to life without parole inside of a high-security California prison.

Several thoughts have come to pass. Is he inherently evil? Certainly there’s an argument to be made. Had he gone crazy and desperate? Since we were best friends, and considering our debauchery together, am I too inherently evil? Which, I don’t believe to be true. Perhaps we become what we nourish, society quick to forgive the criminal antics of a juvenile, but not so much with a man and his murder. Interesting in that we both joined the Corps, and where he failed I in turn flourished. What I know of my time in the Corps: we are a rag-tag group of war fighters, comprised of both good and bad men intent to keep evil at bay. Which again, existentially speaking, puts into question my nature. In killing other men, I would sleep easy. In killing his mother, does he? I wonder if he still dreams? Or are his nights full of monsters? Was I there at the turning point of his life, like the night when we stole a truck to drive to Portland and, of all things, watch an Ozzy Osbourne concert? Was it the night he dropped acid? The list goes on, and does it even matter? He nourished the evil inside, his nature be damned. Although I too feel the evil, always near, I drop to my knees and pray to a God that I hardly believe in. An illusion perhaps that allows our species civility and life, that governs demonic desires. Perhaps mankind is inherently evil or good, some percentage of both? Who really knows? Pondering the meaning of life is an exercise in futility. We live, we laugh, some murder, and in the end we all die.

I remember his laugh, and wonder whether it held joy or cruelty. If he ever knew love? If we were ever really friends, or associates in crime?

Has he since examined his life? Have I, and have you?

One night I’ll never forget: we were juniors in high school, and I was spending the night at his house, which wasn’t often. Judy and her husband went off to bed. Before long they were having sex. It was obvious. Tony and I were sitting in front of the television set, high on weed. The living room was dark, just the glow of the television set. He grabbed the remote control, and turned down the volume, which had the effect of amplifying the sounds from the master bedroom. He looked at me, and didn’t break eye contact. Just looked at me with the dead and hateful eyes of a Rottweiler, and didn’t say a word. Looked at me until I got up and walked away, into the bedroom, closing the door. Was he embarrassed? Did he hate his mother for loving another man? Who knows, but after all these years I know the look in his eyes while he waited for his mother to come home from work. How he sat in the darkness with the television on and the volume turned down. Sat for her, and waited.